Collaborative Group Ritual created for The Level 9 Professional Diploma in Art and Ecology, The National College of Art and Design

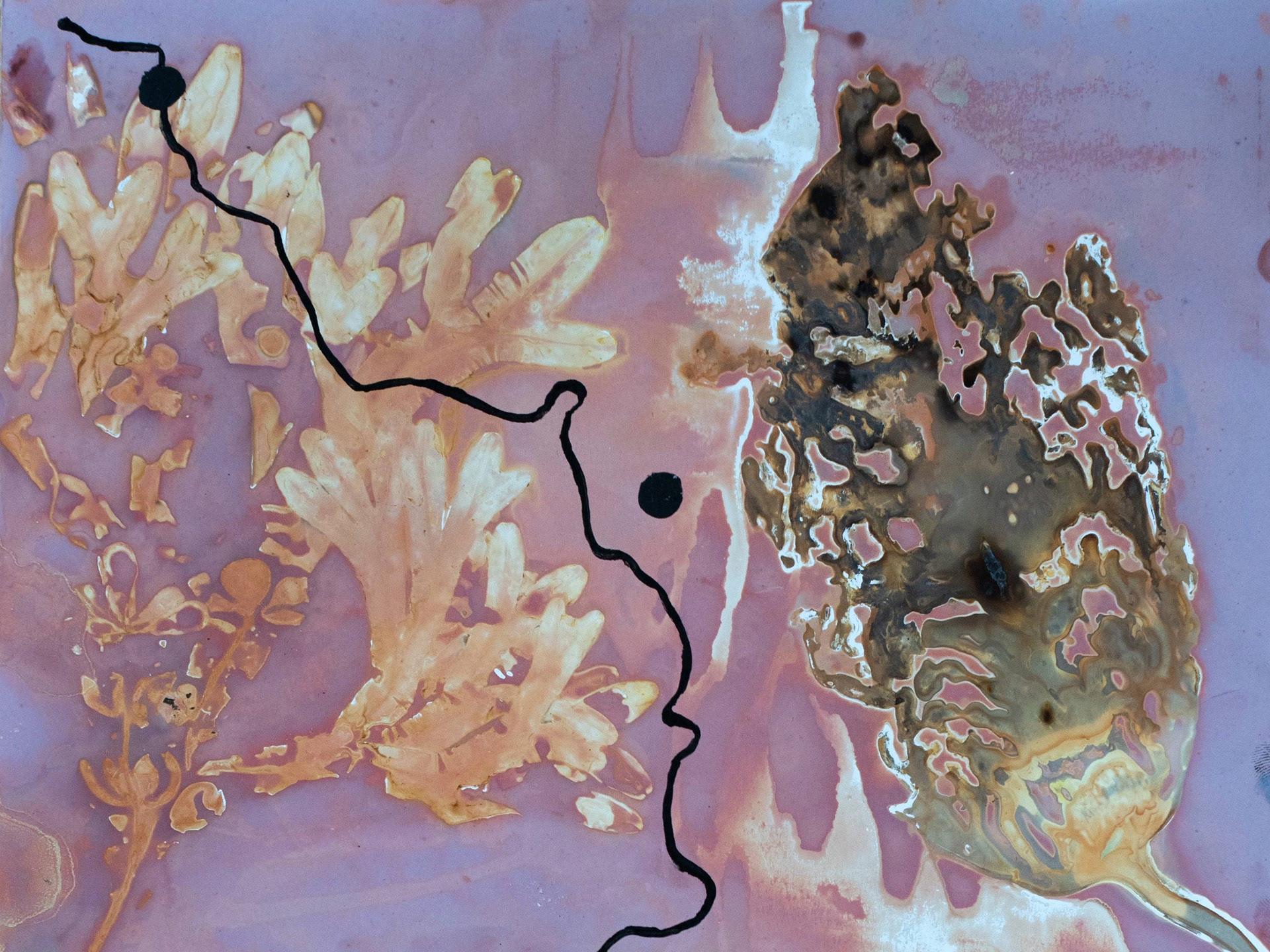

This collaborative group project, created by Marguerite Quinlan, Fiona Flinn, and Maria McSweeney, centered around a ritual piece inspired by their in-depth research into two species: the teasel and the spider.

The ritual began with a musical group procession with banners and using the teasel as an instrument. They moved from a cluster of smaller teasels to the "Mother Teasel," traversing the landscape of the field. Upon arrival, they offered their teasel instruments to the Mother Teasel as a symbolic gesture. Additionally, they collaboratively crafted with the group a circular woven wool piece, which they presented as an offering to "Grandmother Spider."

Participants were then invited to create individual woven pieces using handmade looms and plant materials gathered from the field. These personal creations were also offered to the teasel and spider.

Throughout the ritual, each of the three artists contributed their voice by reading original written pieces. Marguerite, Fiona, and Maria wore handwoven dresses and headscarves printed with motifs representing the teasel and spider, visually connecting them to the themes of their work.

Maria's written piece delved into the historical connections between the spider, the teasel, and industrial textile production. She explored the intricate parallels between these species and the art of weaving, reflecting on their shared histories within the industrial weaving traditions of the Liberties and beyond. Her words invited participants to envision a more sustainable future for textile production, one that challenges the exploitative practices of industrial capitalism. She delivered her piece while the group engaged in crafting their own woven looms, using natural materials gathered from the field site

Performed:

The NCAD Field as part of the Level 9 Professional Diploma in Art and Ecology.

Images by Laurel Fiszer Storey